I still remember the first time I sat across from a brilliant PhD researcher who had just disclosed a new technology to the university’s Technology Transfer Office. It was a novel biosensor, designed to detect early signs of infection faster than current diagnostic tools. The researcher was passionate, the science was sound, and the potential impact was enormous.

But there was one problem: no one had asked a customer if they actually needed it.

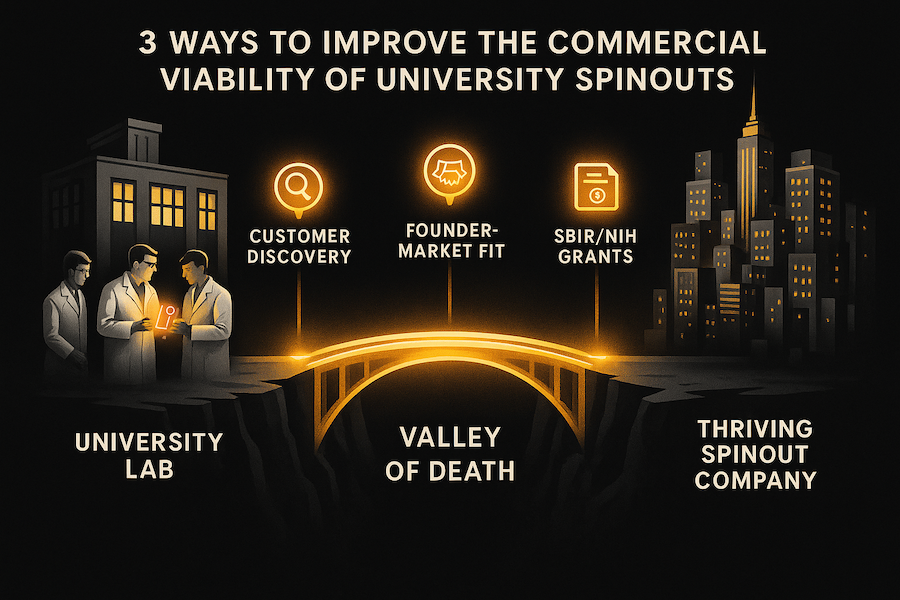

This wasn’t an isolated case. In fact, I’ve seen dozens of similar stories play out. University labs are the engines of breakthrough innovation, yet a vast number of discoveries never make it out of the lab and into the market. They fall into the infamous “valley of death” between research and commercial viability.

The good news? It doesn’t have to be this way. Based on my work with academic institutions, here are three strategies that can dramatically improve the success rate of spinouts.

Strategy #1: Integrate “Customer Discovery” Before Filing

With the biosensor project, the first step wasn’t drafting a patent—it was interviewing clinicians. We discovered that while the technology was impressive, hospitals already had a diagnostic workflow that was hard to displace. The real unmet need wasn’t speed, it was cost and portability.

This is why “customer discovery” must come before a patent filing. Too often, universities fall into the tech-push model: a great invention gets patented and then someone goes looking for a market. By that point, the university may have spent tens of thousands of dollars on IP that no one is eager to license.

Instead, researchers should be trained in Lean Startup methods—hypothesis testing, stakeholder interviews, rapid iteration—before committing resources. It’s not about dampening enthusiasm, it’s about ensuring that brilliant ideas land where they can make the biggest difference.

Strategy #2: Focus on “Founder-Market Fit,” Not Just Tech-Market Fit

The second challenge with the biosensor team was the founder dynamic. The lead researcher was deeply committed to the lab, not to building a company. She admitted, “I don’t want to be a CEO. I want to publish papers.” That honesty saved time and heartache.

This is where universities need to reframe the problem. A great technology with a disengaged founding team is a non-starter. What’s needed is founder-market fit: a team that’s not only capable, but motivated to solve the problem in the world—not just in a publication.

Some universities are starting to create programs that match experienced entrepreneurs with university technologies. These programs allow scientists to stay in the lab while entrepreneurs take on the challenge of building the company. When this match is right, the odds of success increase dramatically.

Strategy #3: Make SBIR/NIH Grant Training Mandatory

Even with market validation and the right team, spinouts face another hurdle: funding. Venture capitalists rarely invest in raw university IP. The first lifeline is almost always non-dilutive federal grants like SBIR (Small Business Innovation Research) or NIH (National Institutes of Health) programs.

But here’s the catch: writing a successful SBIR proposal is an art. Many researchers don’t know where to start, and Technology Transfer Offices often lack structured training. That’s a missed opportunity.

When universities make SBIR/NIH grant training mandatory for spinout teams, they give them an immediate competitive edge. I’ve seen spinouts secure millions in federal dollars this way—capital that doesn’t dilute equity, yet buys time to refine technology and validate markets.

Conclusion

The biosensor story has a happy ending. After rethinking the approach, the team pivoted toward low-cost, portable testing for field clinicians. An entrepreneur-in-residence took the lead as CEO, and the spinout went on to win a significant SBIR award.

This isn’t just one story, it’s a blueprint. Bridging the lab-to-market gap requires a proactive approach:

- Validate markets early.

- Build founding teams with true entrepreneurial drive.

- Master the non-dilutive funding landscape.

University labs will always be engines of innovation. But with the right support, they can also be engines of economic impact.

If your institution is looking to strengthen its commercialization program, I’d love to help.